Joined the laboratory in 2004

- BS, Physics, The Ohio State University, 1993

- PhD, Physics, University of California, Berkeley, 1999

- Theoretical nuclear astrophysics

Research

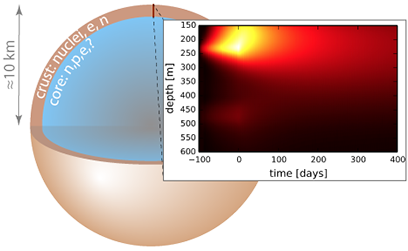

Formed in the violent death of a massive star, neutron stars are the densest objects in nature. Their cores may reach several times the density of an atomic nucleus. As a result, neutron stars are a natural laboratory to study dense matter in bulk. We have observed neutron stars with telescopes, captured neutrinos from the birth of a neutron star, and detected gravitational waves from a neutron star merger. These observations complement laboratory studies of matter at super-nuclear density. My work connects observations of neutron stars with theoretical and laboratory studies of dense matter. Many neutron stars reside in binaries and accrete gas from their solar-like companion. The weight of this accumulated matter compresses the outer layer, or crust, of the neutron star and induces nuclear reactions. These reactions power phenomena over timescales from seconds to years. By modeling these phenomena and comparing with observations, we can infer properties of dense matter in the neutron star’s crust and core. Recently, we have set a lower bound on the heat capacity of one neutron star and inferred the efficiency of neutrino emission from the core of another. We have also calculated, using realistic nuclear physics input, reactions in the crust of accreting neutron stars. These calculations quantified the heating of the neutron star from these reactions, and the results have been used in simulations of the “freezing” of ions into a lattice in the neutron star crust. A surprise from these simulations is that the “ashes” of these bursts chemically separate as they are compressed to high densities. This may explain the inferred high thermal conductivity of the neutron star’s crust.

Biography

A native of Ohio, Brown did his undergraduate studies at the Ohio State University. He then earned a Ph.D. in 1999 from the University of California, Berkeley, under the supervision of Prof. Lars Bildsten (now a permanent member of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, UCSB). While at Berkeley, Brown was supported by a NASA Graduate Student Fellowship. Upon graduating, he was awarded an Enrico Fermi Fellowship at the University of Chicago, where he worked in the ASC Center for Astrophysical Thermonuclear Flashes. In 2004, Brown moved to Michigan State University to join the Physics and Astronomy faculty, with a joint appointment in the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory. He is affiliated with the Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics, an NSF Physics Frontier Center. In 2018, Brown became Associate Chair of the Department of Computational Science, Mathematics, and Engineering (CMSE) at MSU. He is currently serving as interim Chair of CMSE.

Brown's research interests include stellar and nuclear astrophysics, especially related to compact objects and stellar explosions. In his free time, he enjoys running and cycling.

How students can contribute as part of my research team

The study of neutron stars and the dense matter in their interior is in a golden age. New observations have revealed a wealth of phenomena, from pulsations to explosions on their surface. Gravitational waves—ripples in space-time—have been detected from merging neutron stars. Novel experiments and state-of-the-art computing are providing a more complete picture of matter at near-nuclear densities. Our group models the structure and evolution of neutron stars; by comparing our models to observations, we explore what we can learn about the nature of their deep, dense interiors from nuclear-powered phenomena that we observe from their shallow outer layers.

Scientific publications

- Rapid Neutrino Cooling in the Neutron Star MXB 1659-29, E. F. Brown, A. Cumming, F. J. Fattoyev, C. J. Horowitz, D. Page, and S. Reddy, Physical Review Letters, 120, 182701 (2018).

- Lower limit on the heat capacity of the neutron star core, A. Cumming, E. F. Brown, F. J. Fattoyev, C. J. Horowitz, D. Page, and S. Reddy, Physical Review C, 95, 025806 (2017)